“Nee-oo-bon-ga.” As I butcher the phrase for the second time, Mrs. Mkoko and the man bagging my fabric laugh. Stumbling my way over the last two syllables, I train my tongue to hold its place at the back of my mouth, fondly reminded of the ng sound characteristic of my mother’s home language Tagalog. With my third attempt, Mrs. Mkoko claps in approval and I know I got it. I repeat the word one more time as though trying to sear it into my memory and offer up a grateful smile as I collect my change and rejoin the group.

After my first foray into the complexities of siSwati, I receive my first official lesson, sitting outside eating lunch (which consisted of the ever-traditional Swati food at Mrs. Mkoko’s request – pizza). Ears open, hearts warm, we all listen eagerly as she tries to teach us more useful phrases. We ask how to say “hello” and “please” and “thank you” and nervously laugh when we get overambitious and Mrs. Mkoko prompts us to repeat entire sentences after her. I rack my brain trying to make sense of the words, making a breakthrough as I realize the presence of ni indicates plurality of the target audience. For example, ninjani and oonjani mean “how are you?” but the former would be asked to a group. The response to these questions are significantly harder to unravel, so I don’t. I grimace slightly as I trip over the words for “good, and you?”.

In Swaziland, nearly everyone speaks siSwati and English, though many speak other languages for work or school. The influence of neighboring countries have led to a diffusion of cultures and the languages have seeped into the tiny country of Eswatini, like Portuguese from Mozambique or Tsonga from Northern S. Africa. Swati is the national language spoken and written in most homes and English is an official language used often in schools and workplaces. Mrs. Mkoko tells us French is a popular third language to learn as her children have, though she has taken to the isiZulu language, native to the neighboring KwaZulu-Natal province in South Africa.

Our bus drivers from Johannesburg to Mbabane also spoke Zulu, as did the Swazi border post agents they spoke with to expedite our passport check. In fact, from my seat at the back of the bus, I overheard the humble confession of our drivers to speaking a total of six and seven other languages, respectively. They explained it was helpful to know many languages in South Africa, but the hardest part is knowing when and where to use them. Different scenarios lend themselves to different languages, and most vary in popularity regionally.

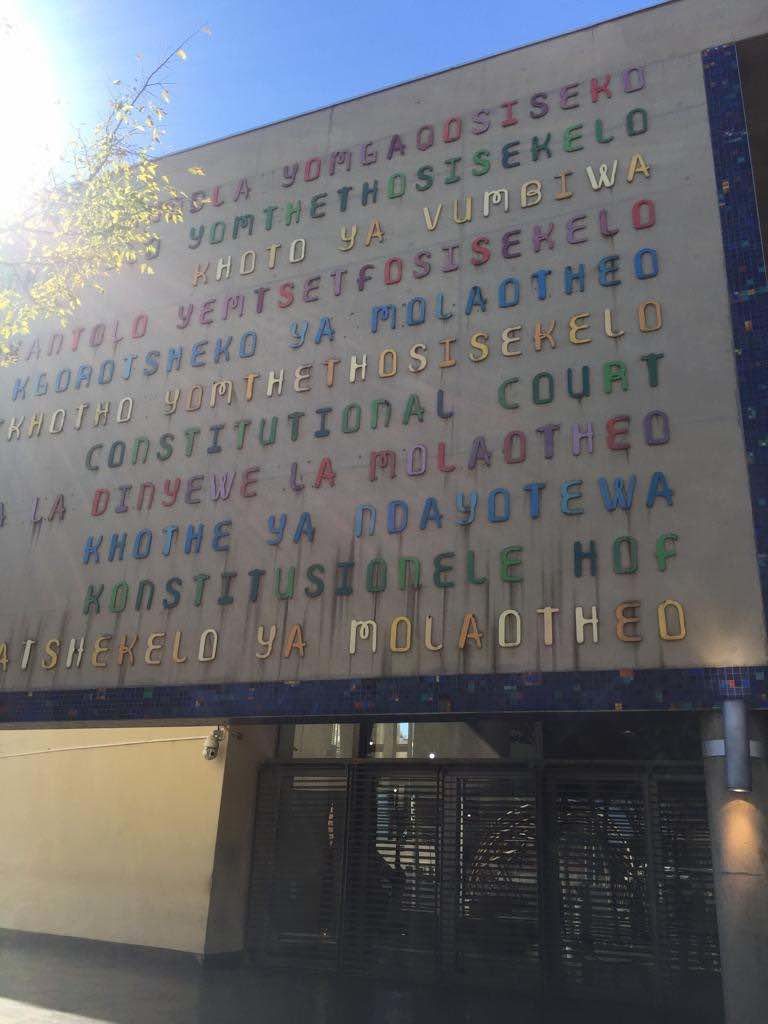

South Africa has 11 official languages, which we learned from our tour guide at the constitutional court (of which she can speak five). On the numerous colored phrases displayed on the exterior of the building, she explained that the words “constitutional court” are written in each of the official languages, purposefully displayed in random order to symbolize that no one language is more important than the other; they are all of equal importance and value. Having visited the Apartheid Museum, Hector Pieterson Memorial, and Mandela House to learn about the country’s fragmented past, this statement was especially telling of their current commitment to moving forward and mending relations between cultural groups, apparent in every detail of the courthouse.

Back in Eswatini, Mrs. Mkoko explains the nuanced differences between siSwati and isiZulu, which she explains are very similar, though “siSwati is much harder”. We nod along as she gets us to pronounce a ts sound that is usually replaced by a ss sound in Zulu. Other sounds our group has difficulty repeating are the barely-there clicks that are employed where there is a written “c”. One of the friendly faces we pass on the way to dinner has a beautiful name pronounced with a click at the beginning. I’m often nervous to mispronounce her name, so instead I mumble a “Hello, thank you”, humbled by my inability to do something as simple as say her name.

I’m ashamed to admit I can (on good days) only speak 1.75 languages – English, passable Spanish, and terrible French. Some of us are a little more well-versed in the multilingual culture of South Africa and Eswatini; Jaz dreams in Spanish and English, Kellen spent a summer in Japan for a fellowship, Heeral knows a bit of Hindu and Gujarati. Lucy is L5 material in German and Wanjiku speaks Swahili at home. Megan and Helen regret taking French and Spanish, respectively, but will be sticking it out through one more semester. Jordan hasn’t decided what language she’s going to take, but is considering Indonesian.

Add us all together and we still can’t compete with the eleven languages of the front doors at the Constitutional Court. Individually, we certainly do not meet the apparent four language minimum of both Swazis and South Africans, but we’re learning. Maybe not necessarily the languages themselves (sorry Mrs. Mkoko, I’ve been practicing, I promise!), but we’re learning about the culture of two countries with incredible propensity for celebrating multiculturalism without giving up personal pride of culture. As we near the end of our first week in Mbabane, I reflect on the crazy and amazing experiences we’ve had so far and can speak on behalf of the nine of us: to our tiny friends on their way home from school that wave as we cross the street, the kind man who helped me figure out the bread slicer at Pick n Pay, Mrs. Mkoko who is opening her home to our mismatch band of Yalies – ngiyabonga. Thank you.