The seventh day we were in South Africa, we toured the Constitutional Court— the equivalent to the Supreme Court in the United States. The two could not be more different in appearance. Where our monolithic white marble pillars and palatial halls insist on greatness at every opportunity, South Africa memorializes their twisted and painful past. This attitude reveals itself in everything from the old weathered bricks used for walls in the courtroom, remnants of the former prison here on what is now Constitution Hill, to the small window winding around the courtroom that allows the justices to view the feet of their citizens walking by, their heads at ground level so as to literally serve at the feet of the people.

The court tour ended at the entrance to a hallway where art is displayed, allowing us to go on alone and absorb each piece in our own time. There was a mix of framed photos, paintings, and sculptures, a mix of violence, loss, resistance, hope: an overwhelming ache as the display turned the past over in open palms. Already this week our class had explored the Apartheid Museum, the Hector Pieterson Museum, and Nelson Mandela’s former home. I had only just begun to find my footing in South African history and to walk the path to understand this complex story and the many different people who call this place their home. Nonetheless, South Africa had quickly endeared itself to me; I felt a sense of intimacy with this country that leaves its heart wide open.

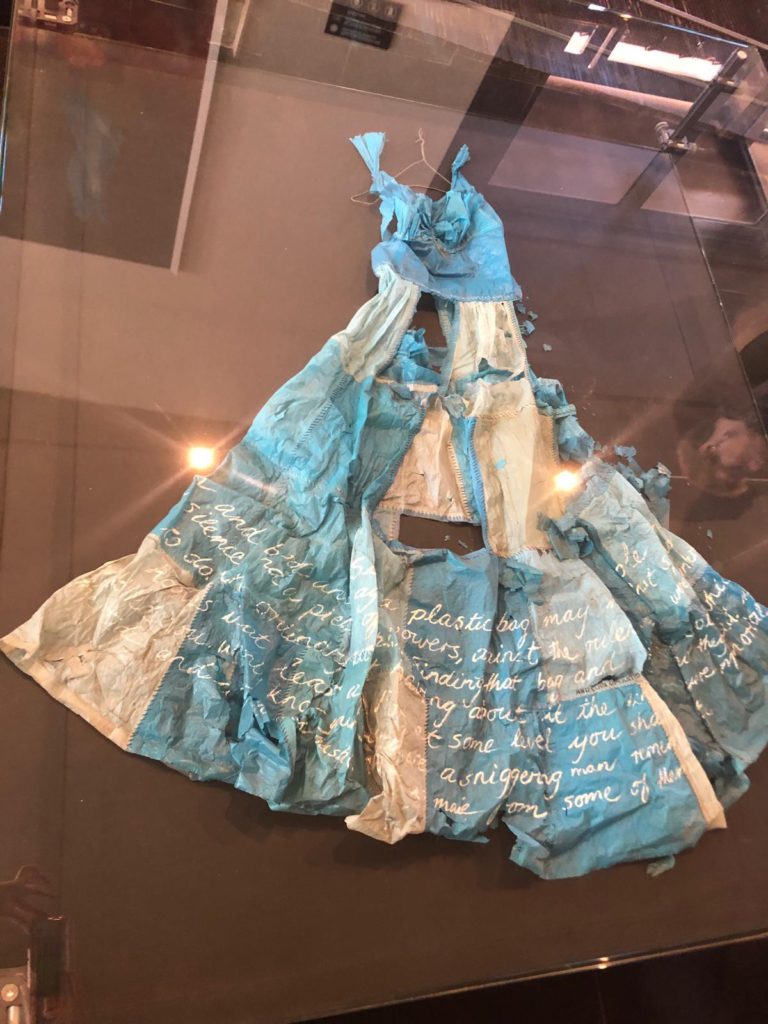

And so, before reaching the blue dress, I had been turning all of this over in my mind, feeling equal amounts of emotional exhaustion and a searing gratefulness. We reached the display as a group; three dresses laid flat in glass cases under two large paintings, each painting depicting the dress suspended in air, flowing in front of a dramatic background. I stood over the first dress on the right. The placard read, The Man Who Sang and the Woman Who Kept Silent. Varying sky blue squares were patchworked together: a simple dress made entirely of bright blue plastic grocery bags. The bottom of the skirt was carefully fanned out to expose a painted on message in lilting white cursive letters that was not quite readable.

What was the meaning of this blue dress? To me, at that point it was still just a shitty blue dress stitched out of plastic grocery bags.

The Man Who Sang and the Woman Who Kept Silent tells the story of Phila Ndwandwe and Harald Sefola, two high-ranking members of the liberation movement captured by the Security Police. Harald Sefola, “the man who sang,” defied his captors by singing Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrica just before they cruelly murdered him. He was described by his murderer as “a strong man [who] believed deeply in that in which he was involved in and of its correctness”. Phila Ndwandwe is “the woman who kept silent,” the woman who the story of the blue dress revolves around. Upon being put in captivity, she was stripped of her clothing and left naked so that she might inform on her comrades. In the room she found a single blue plastic bag, which, having nothing else, she fashioned into panties in order to cover herself, to preserve her dignity. She too was murdered after a few weeks— but stayed silent throughout. Both of these stories were told in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) hearings. About Phila, one of her killers stated, “She simply would not talk…God she was brave.”

Artist Judith Mason, upon hearing the TRC story broadcasted on the radio, was prompted to make the dress out of blue plastic grocery bags, and later followed with the two paintings. The message scrawled on the skirt of the dress is described by Mason as “a sort-of love letter to Phila”. I have included it below.

“Sister, a plastic bag may not be the whole armour of God, but you were wrestling with flesh and blood, and against powers, against the rulers of darkness, against spiritual wickedness in sordid places. Your weapons were your silence and a piece of rubbish. Finding that bag and wearing it until you were disinterred is such a frugal, common-sensical, house-wifely thing to do, an ordinary act… At some level you shamed your capturers, and they did not compound their abuse of you by stripping you a second time. Yet they killed you. We only know your story because a sniggering man remembered how brave you were. Memorials to your courage are everywhere; they blow about in the streets and drift on the tide and cling to thorn bushes. This dress is made from some of them. Hamba kahle. Umkhonto.”

My classmates and I were gathered around the glass case, peering down at the tattered dress, as my professor told us the story and read this message/poem/love letter out loud. The shitty blue dress was filled with meaning now, and at the word “sister”, I felt my chest tighten, my heart threatening to collapse on itself. “Sister” immediately suggests a closeness, an unquestionable love, and in that moment she was my sister too. I felt her pain, her humiliation, her soaring bravery, and my heart swelled with her “ordinary act”, the small, small thing that let her take something back and defy the people who savagely tried to beat her down. The trash at the bottom of her cage, the blue plastic bag, became a symbol for so much more—for a woman whose silence echoes loudly today, for the enduring defiance of generations of the oppressed, for the hope left remaining after each tide of loss, for the growing pains of a country that is fighting to keep one eye on the past and both feet pointed to the future.

Final Note:

Douglas Ainslie, a law clerk of the Constitutional Court, researched this story in-depth after being touched by Mason’s work displayed in the court, and he published his findings in an article titled Art, the TRC and the ‘Truth’: Unstitching the ‘Blue Dress’. What he found was that the story of Phila Nkwandwe using the plastic blue grocery bag as makeshift panties is, at the very least, unlikely to be historically factual. Judith Mason responded to this article with an intimate piece of writing herself, Unstitching the Blue Dress: A Response, which details her artistic process in the pieces as well as a response to Ainslie’s findings. It is a remarkable conversation about the necessity of historical accuracy versus the way art and a story will take a life of its own, becoming an irrevocable symbol that far exceeds its origins. And if you’re curious, you can access the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Amnesty hearings here.